Two current exhibitions, a workshop we recently organised at DaDaFest, and the ongoing controversy around “bladerunner” Oscar Pistorius’ inclusion in the Olympics have got me thinking about developments in human enhancement technologies and the impact on disability politics.

The athletic success of double-amputee runner Oscar Pistorius has propelled this discourse into the mainstream. Some say the blades he runs on give him an unfair advantage, allowing him to push off the ground more efficiently than a normal human ankle. This discussion of whether Pistorius, until now regarded as a “disabled” athlete, is in fact an “enhanced” athlete is an extraordinary development, and represents a major milestone in the development of prosthetics technology. Some writers, such as bioethicist Andy Miah, have pointed out that it has an even greater significance: “… the rise of technological enhancements means that prosthetics can overtake the capacities of biological body parts and what we consider today to be optimal may, tomorrow, seem inefficient.” It is easily conceivable that different prosthetics and enhancements may give other Paralympics athletes advantages to the extent that they begin to produce faster, further, stronger, more accurate performances than athletes in the non-enhanced Olympics.

Some of the historical background to this type of speculation is explored in the Wellcome Trust’s ‘Superhuman’ exhibition, which opened in London recently and runs to October. It suggests that “scientific developments point to a future where cognitive enhancers and medical nanorobots will be widespread as we seek to augment our beauty, intelligence and health”, and does so through displaying medical, scientific and cultural artefacts which humans have used to make themselves better from early times, from an Egyptian prosthetic toe and a nose prosthetic for a 19th century syphilis victim, to modern cosmetic surgery, i-Limbs and futuristic promises of nano- and biotechnology.

Yet the vision of a bionic future jars with the reminder, in another part of the exhibition, of the artificial limbs used to “normalise” – but certainly not to enhance – thalidomide children. While there may be a gradual trend to more functional prosthetics adapted for the individual, in reality many disabled people’s experience of prosthetics is still uncomfortable, limiting and frustrating.

The notion of enhancement, of making ‘superhumans’ of disabled people, presents problems for what has been the prevailing discourse in disability politics in the English-speaking west, which centres on the social versus medical models of disability. In this discourse, there is a “medical model of disability” which sees the disabled person as a problem, to be adapted, cured or shut away. Against this, the “social model of disability” considers disablement to be created by the way that society and the physical environment have been structured, and to have little to do with impairment itself. Using this model, the ‘cure’ to the problem of disability lies in the restructuring of society. This position became increasingly rigid in the UK during the 80s and 90s, with corresponding suspicion – indeed hostility – directed at health and medical science professionals, who might wish to cure or prevent those impairments that are part of a person’s identity.

In 2006, sociologist and disability activist Tom Shakespeare suggested in his book ‘Disability Rights and Wrongs’ that the disabled people’s movement needed to move on from this polarised position. He proposed an alternative account of disability, which takes into account the interplay of individual and contextual factors. In other words, he argues that people are disabled by society and by their bodies, and therefore that it is important both to prevent impairment and to support the rights of disabled people.

An exhibition currently showing at Bluecoats Gallery, Liverpool, as part of DaDaFest, makes an interesting contribution to this more nuanced approach to disability, exploring themes of technological enhancement, conformity, and normality. ‘Niet Normaal’ is a new version of an international exhibition that explores the questions ‘What is normal?’ and ‘Who decides?’ through the work of contemporary artists. The Liverpool version, curated by Ine Gevers and Garry Robson, recognises that technology is generating new opportunities for people of all sorts, shapes and sizes, but sets this against the striving to become ever more uniform, ever more ‘perfect’.

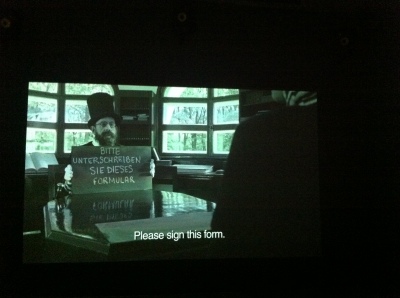

Javier Tellez’s film Caligari und der Schlafwandler (Caligari and the Sleepwalker) is a delightful homage to Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919), a film that has been interpreted as a commentary on the German people’s somnambulist response to the rise of the Nazis. In Tellez’s version, psychiatric patients play the characters. The story of the doctor’s “discovery” of a sleepwalking alien is beautifully produced and raises questions about what we perceive as mental illness and how we communicate our complex internal worlds. Don’t we all hear voices some of the time?

In the next gallery, a vast glass-covered table holds a collection of 14,000 pills. Pharmacopoeia’s Cradle to Grave II is the outcome of a study into the use of medicines by the average Dutch person, but is bordered by photographs and objects from daily lives. If these are the “normal” relatively healthy people, what does this vast intake of powerful medication imply for how we understand our own wellness?

Imogen Stidworthy’s video installation focuses on the speech therapy of photographer Edward Woodward, who lost his voice in an accident. The strain of his production of words is felt through vibrations on a bench. The fact that the words he is struggling to pronounce are those in the title of the piece, I Hate, suggests his anger at his debilitating situation.

As someone with a fair amount of titanium in her body, I was entertained by Floris Kaayk’s video Metalosis Maligna, a mockumentary about a disease that affects patients with metal-based implants, eating away the human tissue as the metal takes over the body. The CGT work is impressive and there are some very comic moments. It’s also showing in the Superhuman exhibition.

I was at DaDaFest for the fourth project of an Arts Catalyst programme strand, Specimens to Superhumans, a collaborative project with Shape, a disability-led arts organisation. Specimens to Superhumans aims to provide a series of creative spaces for disabled artists to engage with contemporary issues around biomedical science and ethics. The activities have included artists’ commissions, panel discussions and practical creative workshops.

At DaDaFest, we organised a 2-day film-making workshop for disabled artists and film-makers, led by writer/director John Williams. The intent of the workshop was to create short films that imaginatively addressed themes of disability, bioethics and prosthetics. John Williams’ films combine live action, animation and visual effects, engagingly dealing with highly sensitive subjects. His award-winning film Robots – The Animated Docu-Soap (2000) tells the story of three redundant robots who, having acquired disabilities or mental illness, attempt to reassert meaning to their lives, while in Paraphernalia (2009) a young boy gets annoyed with the little robot that follows him everywhere, but the robot is more than just a toy and turns out to be the object on which his life depends.

The two short films produced by the participants in less than two days – Side Effects and The Experiment – will be showcased at DaDaFest Film Shorts on 21 August 2012, at FACT, starting at 5pm. We also hope to put them online – so watch this space.

John Williams, Robots – The Animated Docu-Soap (2000)

John Williams, Paraphernalia (2009)